Combining seasonal forecasts with weather generators is a suitable approach to estimate climate risks for the coming weeks or months.

Local climate variability depends on global climate patterns, thousands of miles away.

Some of those “teleconnections” are persistent, recurrent and covering a wide spatial scale, such as whole continents or even larger areas.

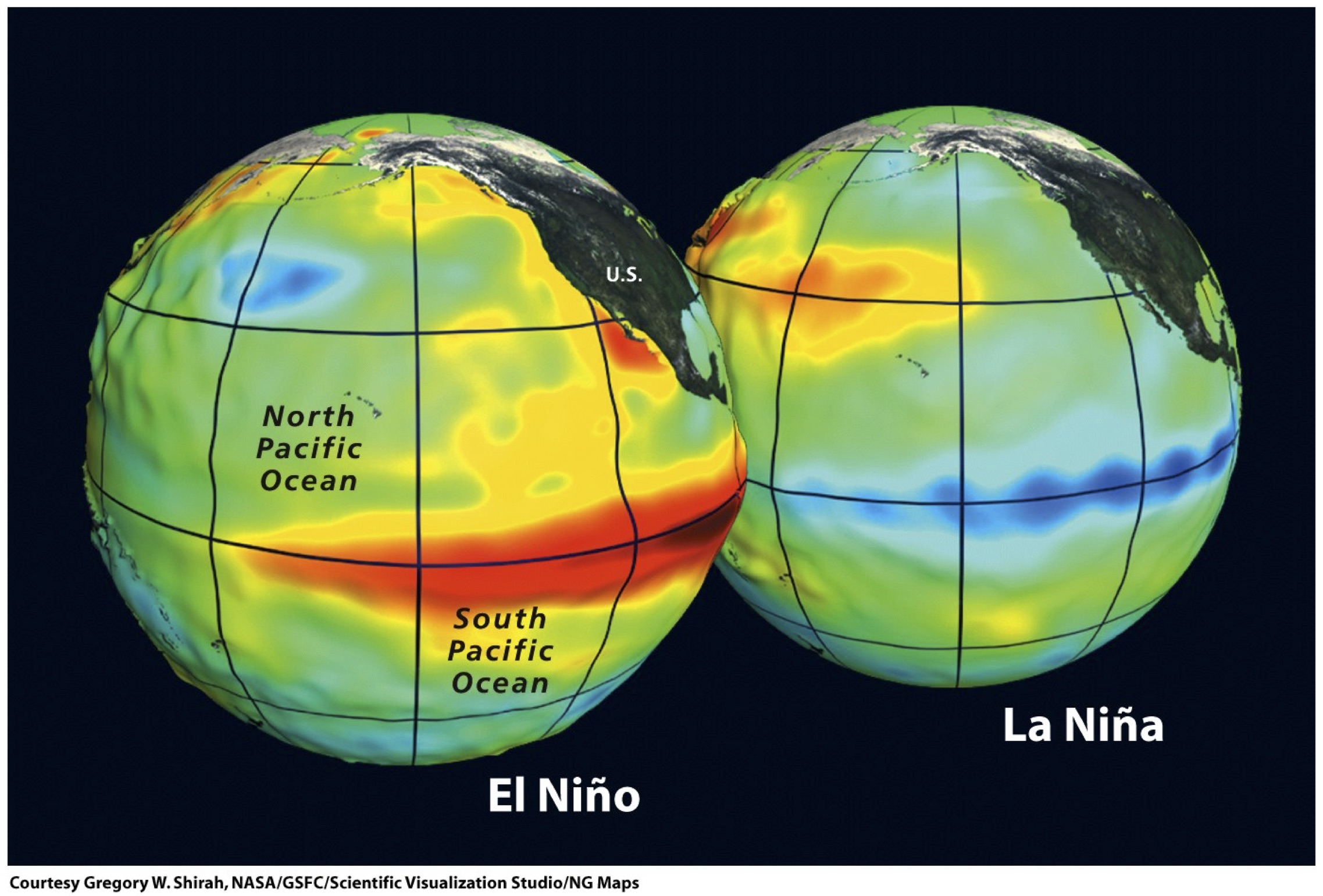

Perhaps the most important climate pattern, significantly influencing global climate variability, is the phenomenon known as “El Niño – South Oscillation” (ENSO).

ENSO is a periodic cycle of ocean-atmosphere interaction, meaning abnormal temperature rises in the Pacific Ocean waters, near South America.

Whereas El Niño brings warm waters in central Pacific, La Niña is just the opposite. ENSO changes completely the wind currents in the ocean, bringing important consequences on a planetary scale.

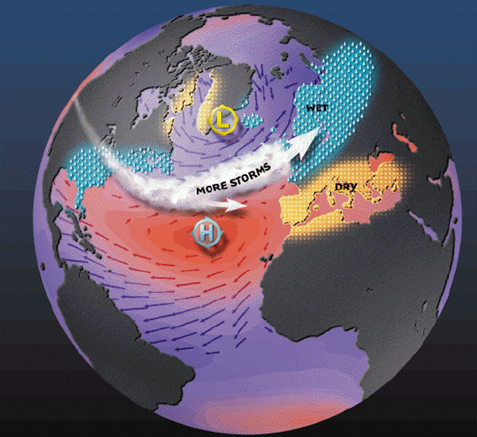

Besides ENSO, there are other global patterns influencing climate variability. In Europe, for instance, the influence of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NOA) is more important that ENSO.

The NAO consists of an increase or decrease in the atmospheric pressure difference between Iceland (low pressures) and the high pressure on the Azores (Azores anticyclone).

In the NAO positive phase the pressure on the Azores is very high and over Iceland very low. It brings storm weather to Northern Europe and decreasing rainfall to Southern Europe. During the NAO negative phase the effect is just the opposite.

Seasonal forecasts rely on predicting the behaviour of global climate patterns as ENSO or NAO

The CLIVAR program, sponsored by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) promotes identification and characterization of “teleconnections” between global climate patterns, such as ENSO and NAO, and local weather. It especially encourages the improvement of forecasting skills.

The seasonal forecasts depend on verified teleconnections, as well as on the indices related to ENSO, NAO and other global patterns.

Many international institutions and national meteorological services provide seasonal forecasts.

In most cases, the forecasts show the probability of tercile categories. It means, for instance, above the mean, near the mean or below the mean, according to the probability distribution.

The UK Met Office provides such seasonal forecasts.

As can be seen, the three-months forecast indicates higher probabilities for temperatures above the mean.

Seasonal forecasts are very useful for specific climate impact assessments. For instance, EU JRC provides estimates of wild fire probability index in a ten-days ahead basis, combining temperature and rainfall anomalies according to the ECWFM seasonal forecast.

The spatial resolution of seasonal forecasts limits their application in local climate impact assessments. However, they could be combined with weather generators, obtaining synthetic series of precipitation, temperature and other meteorological variables.

These series are statistically equivalent to a local series, but perturbed according to the seasonal forecast probability. The “realizations” of synthetic weather are used to assess climate impact in vulnerable activities, in the same location of the historical series provided to the weather generator.